The Evolution of Pelagic Australis

It’s been 15 years since Pelagic made her maiden voyage into southern

waters. What began as a one year lark to cruise my own boat after two

decades of a peripatetic round on the ocean racing circuit, has evolved into

a lifestyle coinciding with an expedition charter business.

The concept was hatched on the weather rail of the maxi Drum on the last leg of the 1985/86 Whitbread Race. The mind wanders into all sorts of extraordinary scenarios when approaching the end of such an exciting ‘cradle to the grave’ extravaganza and uncertainty of the immediate future always looms large for the crew (at least in those days). Phil Wade and I made a cavalier decision to build our own boat and go cruising. He wanted to sail from place to place catching big fish, while I was interested in the high southern latitudes to climb mountains. Patrick Banfield began to sketch out the design on his off watch, gratis – a simple 48 footer that grew into 54 by the time we reached the finish in Southhampton. On arrival we sent Chuck Gates, office bound in Wisconsin, the tempting proposal to a take a year off. An old sailing friend from Chicago he had been on the Cape Horn leg with us, and now needed little convincing to make up a party of three on a one year each, time share basis.

Pelagic was built DIY in an abandoned shed in the nascent Ocean Village in 1986/87. The salient features were an overbuilt steel hull, lifting keel and rudder for beaching and probing uncharted waters and few amenities other than a warm and cozy interior. Followed a three year cycle, a year each for myself, Phil and Chuck, Pelagic wandering in austral seas including Tierra del Fuego, Antarctica, South Georgia, South Africa, Brazil, Chile, through the South Pacific and on to New Zealand and Melanesia before returning to Tierra del Fuego in December 1990. I was in line for an extra year (again in Antarctica) in the schedule as compensation for the building which was followed by an amicable buyout (we are still close friends after all the usual trials and tribulations of a boat partnership) from Phil and Chuck based on the opportunity I identified in ‘expedition chartering’ in the Southern Ocean environs.

In the late 80’s and early 90’s the rag tag charter fleet based in Ushuaia, Tierra del Fuego consisted of a formidable French armada of six yachts and one American. Kotick, Kotic II, Croix St Paul, Kekilistrion, Baltazar, Ksar and Pelagic were the ‘pioneers’ following in the footsteps of the ‘explorers’ Jerome and Sally Poncet on Damien II.

Expedition rather than tourist based, Pelagic has supported and often starred in 15 documentary film projects from eight countries including two features with Gary Jobson from ESPN. Most of our work is providing logistic support to projects whether they be a Greenpeace audit (1993), Robert Swan’s Mission Antarctica (1998 and 1999) or climbing, trekking and filming expeditions on the order of five to eight weeks duration. This is enhanced by visitor’s trips; sailors making a pilgrimage to Cape Horn and the Beagle Channel and the Antarctic Peninsula the favorites. Our territory is the Argentine coast from Buenos Aires and the Chilean coast from Valdivia – the pack ice defining our limits south.

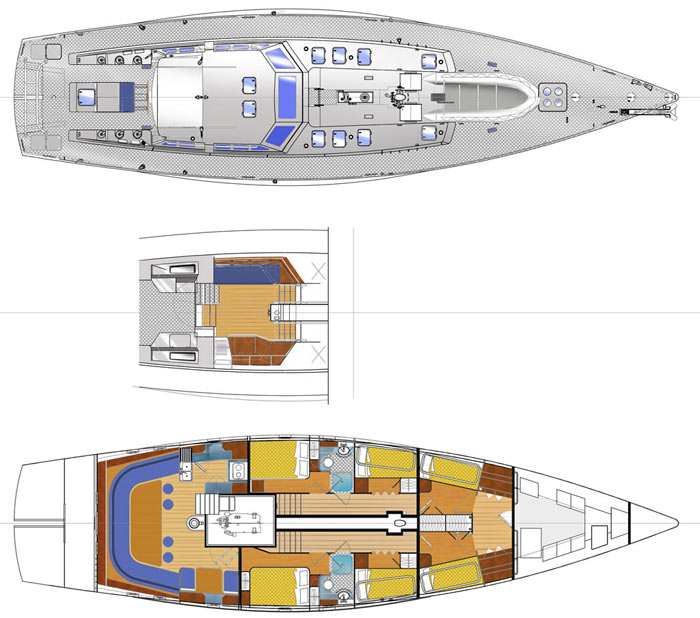

Over the years as demand has increased for adventure travel, coupled with the need for more sophistication, the inevitable has arrived – a bigger vessel. Pelagic Australis at 74 feet LOA is a simple extrapolation of the current Pelagic but differs in three main features: Obviously in size, but also roomier per proportional length to accommodate up to ten passengers with two crew. Second, equipped fully internet capable for sending digital photographs, steaming video and the ability to access web sites, with a dedicated ‘communication suit’ for two people to work in comfort, all of which are now required by media projects. Lastly, she will carry a DNV (Det Norske Veritas) Hull Certification with a CE marking and have an MCA (Maritime and Coastguard Agency) Certificate to carry passengers. This last consideration, a substantial added expense is clearly a future necessity with the general increase in bureaucracy we find in all things. This includes permissions required from the respective Antarctic Treaty nations, regulations governing charter vessels, insurance requirements and general liability issues. The marketing implications are of course positive, as we will become an attractive and cost effective vehicle for government organizations for logistic scientific support. Currently they will not touch you with a barge pole without the necessary paperwork. From a practical point of view Pelagic Australis at 23 meters falls below a MCA threshold of 24 meters and 12 passengers or less. Frankly, more than 8 to 10 passengers is problematic (cooking the pasta for example) in this game otherwise you are in a ‘tour ship’ environment.

|

A more fitting description of Pelagic Australis is to define her as what she is not rather than what she will be, and in many ways the intention is to promote the idea of a go anywhere, do anything cruising vessel. We call her a ‘sailing vessel’ and not a ‘yacht.’ This is a work boat first and foremost. To achieve this should be easy, but designer Tony Castro was correct when he warned me in the beginning stages, “In many ways it will be more difficult designing a simple boat compared to the norm.” He will agree with me that this was an owner rather than a designer led project (In his defense, to some eyes, I have to take credit, or the blame, for the plumb stern I insisted on). I knew exactly what I wanted and the formula was very pragmatic – keep it simple! The first meetings went something like this, “Do you want a bow thruster?” NO ‘Hydraluic furlers?” NO “Electric winches?” NO “Watermaker?” NO “Refrigeration?” NO, NO, NO, and so on. I am amused again and again when I see the astonished faces of the suppliers of equipment when they realize we intend to trim our sails and furl them - by hand!

A go anywhere do anything cruising vessel!

The only two ‘gadgets’ which are really fundamental are the lifting ballast keel and rudder, both in swing configuration. Keeping the same concept as the current Pelagic, a system that has never failed in 15 years of operation, the keel is raised in about two minutes by a wire tackle and a 24 volt tow truck winch, the kind you would have on the front of a Landrover. We have improved the bearings and the hold down mechanisms using mast compression, but little else has changed. The swing rudder is fully manual, can be raised in seconds, by releasing a brake band and raising the blade past the horizontal (skeg depth) with a fixed, in place handy billy. Quick systems like these allow you to be creative in cruising shallow waters, avoiding bergy bits and growlers in Antarctic anchorages and having the ability to beach and dry out – all of the above giving you maximum flexibility and therefore an added margin of safety.

Pelagic Australis is a sailboat and not a motorsailor – the latter a concept which I consider neither fish nor foul. When we are too old and infirm to hoist the main, then the next logical step is a motor driven vessel. With a conservative cutter rig, she will be a ten knot boat under sail, as well as under power with a fixed four bladed propeller, freewheeling under sail to trickle charge the service batteries via a shaft alternator. Her speed and range will allow her to work both the austral summer and the northern Arctic summer, making the transit up and down the Atlantic twice per year. Reliability, redundancy and low maintenance were the foremost issues and this lack of what I consider gadgetry that seems to be becoming standard issue on smaller and smaller sized craft has produced an inexpensive build for her length and tonnage. Sail handling will be good old fashion muscle power, and this is what our clientle, active pursuits people, like and expect. To follow on, if the skipper can’t handle a 74 footer without a bow thruster then maybe he is not fit for the job. With regards water – where we go there is nature’s own everywhere and we take it from the nearest available waterfall, bow into the trees – magic! Years ago, one American skipper about to embark on a cruise to Antarctica, upon finding out that we had no fridge/freezer asked me, ‘Gee, how do you keep your steaks cold?” He soon found out for himself that the forepeak bilge does the job quite nicely.

After 15 years of maintaining a steel hull, choice of materials was not difficult. Although steel is preferred for ultimate strength and durability in high latitudes, we opted for an over specified aluminium construction at the outset for short and long term cost considerations.

French style, she will be bare alloy above the waterline and the working deck, with a polyurethane paint finish only on the pilot house and the cockpit – the places people lean against, touch and sit on. I see no point in the expense in fairing and painting a hull and then maintaining it over the life of the vessel when in our way of rough handling she is really a 74 foot fender. The fact is, we never go to marinas because there are none, and the commercial docks we bunker at and lay to are rough arrangements and unfriendly. This goes for the deck where a Treadmaster surface over bare alloy margins is all that is required. Ditto for the bilges - no paint except in the engine room. When you add up the costs savings of a bare hull, not to mention the relief of the need all too often in bathing yourself in toxic chemicals to ‘touch up,’ (acetones, thinners, paint, epoxies) the benefits become obvious in lieu of a perfect finish. Most of the other maintenance issues (mechanical, deck gear, sails) can be dealt with underway, as a ship does, but over coating exterior paint surfaces requires substantial ‘down time.’

I am always amazed that so called ‘cruising boats’ are still being designed

flush deck with no protection for the helmsman and crew. In our concept we

started with the pilothouse and then designed the rest of the boat

underneath it. Even in mid latitudes, shelter is an issue for comfort, not

least of all safety. Our house incorporates an inside steering station,

chart table, navigation instruments and a pilot bunk/settee. In dirty

weather at sea or in port I envisage five people milling around in there. It

is also a social ‘get away,’ when you’re fed up with the conversation

listening to so and so around the salon table you can re-group up on the

mezzanine level instead of having to retire to your cabin.

I am always amazed that so called ‘cruising boats’ are still being designed

flush deck with no protection for the helmsman and crew. In our concept we

started with the pilothouse and then designed the rest of the boat

underneath it. Even in mid latitudes, shelter is an issue for comfort, not

least of all safety. Our house incorporates an inside steering station,

chart table, navigation instruments and a pilot bunk/settee. In dirty

weather at sea or in port I envisage five people milling around in there. It

is also a social ‘get away,’ when you’re fed up with the conversation

listening to so and so around the salon table you can re-group up on the

mezzanine level instead of having to retire to your cabin.

Leaving the pilothouse through a watertight door you enter a ‘halfway house’ that is an extension of the pilot house structure, but undercover with seats either side as well as stowage for the safety equipment like lifejackets, harnesses, EPIRBS, flares, etc. Four to five people can be outside, but dry, close to the helmsman. A composite hatch that is full breath of the house roof slides forward under the mainsheet bridle to allow the sun in for fine weather and also allows you walk upright to reach the watertight door.

The helmsman stands just aft of the house and protected from the full blast of wind and sea. Directly to his hand are all the principal sheet control winches and headsail furling lines, mounted on an above-the-knee height coaming with no seats so the winches can be worked most efficiently. The helmsman’s seat is a float free cover for the two 12 man Solas A rafts required by the MCA.

The plumb stern was a commercial ship feature. To my eye it looks ‘the business’ and the increase in aft deck space is substantial. The aft scoop/dive platform accessed by lifting up a hinged composite grating incorporates the lifting rudder mechanism and two spools with floating polypropylene shore warps that can be run ashore unattended by one person in the dinghy.

Forward of the house two coamings or ‘fingers’ built on top of the working deck provide a plinth for the escape/ventilation hatches, dorade boxes and line stowage and continue on forward of the mast to locate the aft end of the inflatable. A single pedestal grinder is mounted on the keel trough at working deck level which is used to initially hoist the mainsail (then this halyard is worked from the winch on the mast), clew in the reefs, doubles as a windless for mooring lines (springs lead to it through a tunnel in the coamings) or can bring in the chain with two chain hooks on pennants in case the electric windless goes down. Lastly, it is a back up system to manually lift the 12 tonne keel with a spectra block and tackle.

Although 74 feet is what I would consider on the edge for a cutter or split rig, we chose a single mast against the benefits of a ketch or schooner simply to eliminate the clutter from an aft rig. With a fully battened mainsail and efficient batten cars and luff track, it should be manageable with two people (and autopilot) sailing conservatively. In any case, the intention when running downwind in a fresh breeze is to drop the main and ‘wing and wing’ the 100% high clewed jib on the inner stay and 60% of the outer high clewed genoa on a double spinnaker pole track and car system. In this way, mistakes in steering by inexperienced drivers are less consequential. The blade staysail with a very hollow leech is used as a storm jib and for heaving to. Four reefs in the mainsail are ‘de riguer’ for the Southern Ocean.

There is little needed in a high latitude interior other than to be warm and dry. 75mm of blown in polyurethane foam

provide the insulation required. Deck fittings are welded in where

possible and the winches are mounted on the coamings, so there are

few deck piercings to leak and wick moisture. The heating system is

the Reflex, a Danish fishing boat system consisting of an attractive

diesel burner pot (doubles as a hotplate) in the main salon and

radiators feeding off it’s back boiler in each sleeping compartment.

The fuel is fed from the day tank by gravity and the water is

circulated by natural convection so no power is required.

There is little needed in a high latitude interior other than to be warm and dry. 75mm of blown in polyurethane foam

provide the insulation required. Deck fittings are welded in where

possible and the winches are mounted on the coamings, so there are

few deck piercings to leak and wick moisture. The heating system is

the Reflex, a Danish fishing boat system consisting of an attractive

diesel burner pot (doubles as a hotplate) in the main salon and

radiators feeding off it’s back boiler in each sleeping compartment.

The fuel is fed from the day tank by gravity and the water is

circulated by natural convection so no power is required.

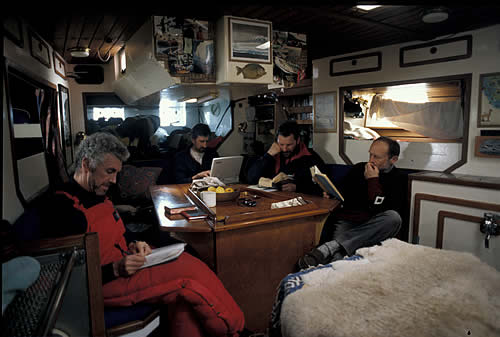

I recently sailed on a 60 foot cruiser that had virtually no storage space – every locker had either a transformer, power pack, pumps, valve chest, ducts and other questionable life enhancing contraptions that would have taken Houdini to access and service. The price tag was 1.5 million pounds for a boat without a locker to hang your foul weather gear. We must ask ourselves what do we really need to go voyaging? Dr. Johnson said “Conveniences are never missed where they were never enjoyed.” Well, it’s too late for that, but I am sticking to my philosophy in planning virtually no ‘appliances’ on board Pelagic Australis (the day you see a VCR down below, shoot me). In place of an electric chopper, blender and microwave we have a crew (I mean the punters) who at meal times are handed a knife and cutting board, grater, a mixing bowl, pestle and mortar, stirring spoon or what ever is required and asked to get on with it. When I see six people sitting at the salon table contributing to the evening meal, content in a mess of potato peels, garlic and onions, sipping wine and happily exhausted after another big day, I know we have struck the right balance. People need things to do and they thrive on it. This is the Pelagic way – keeping it simple on a voyage of participation.